Another installment of “What I’m Listening To”! Today’s piece is Louis Andriessen’s Nuit D’été for piano 4-hands. I was somewhat surprised when this came to my attention because this is not the type of music I think of when I think of Andriessen (I think of things like Worker’s Union, which is a fabulous piece that you should also listen to – it is very loud and angry…not at all like today’s piece, which perhaps shows a mellower side of the composer).

So who is Louis Andriessen? He is a Dutch composer who was born in 1939. His music has been influenced by a lot of disparate sources (including jazz and improvisation). I actually met him briefly at the Royal College of Music in 2005 when he came to talk to the composers – he was having a conversation with Julian Anderson about himself, his experiences, and his music. I am sad to say that I don’t really remember what they talked about (although I did hear Worker’s Union around that time) – but I do remember being told that after the concert of his work (that was very difficult, apparently), he stood up at the back and gave a thumbs down to the (extremely hard-working) singers (one of the singers told me this afterwards…I did not actually see the thumbs down). So maybe he was a bit of a…meanie?

Enough about that – I find it is dangerous to judge people’s music based on their attitudes (although the latter is sometimes reflected in the former). I had a very ethereal mental image of George Crumb until he came to visit Carnegie Mellon and proved to be a very down-to-earth man with a strong West Virginia accent. So now I just listen to the music (as much as possible).

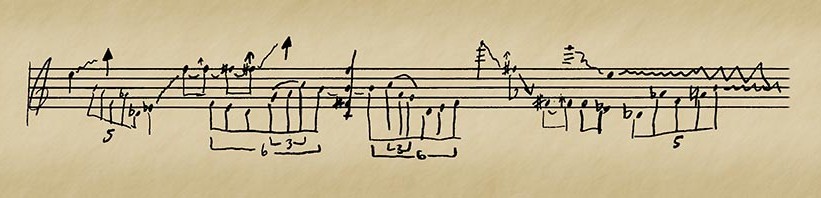

And there is music to listen to here. First thing’s first – this is a fairly early piece for him. It was written in 1957 and is certainly not of the prevailing style of the Darmstadt school (which was into total serialism (a difficult topic to sum up in a parenthesis, but basically where everything from the notes to the rhythms to dynamics, range, timbre was based on pre-written sets – for dynamics, say, you’d have f, p, mp, ffff, pp, mf and so on – you’d repeat them in that order (or a permutation, inversion, or retrograde of that order)…hey – leave me a comment and we’ll discuss it later!)). So what is it? Well – on the surface, it has a fairly simple structure with a clear rhythmic motive to tell the listener what’s happening. The structure is ABA and that rhythmic fragment for the A section is:

You can hear Andriessen juxtaposing contrapuntal uses of this fragment with rich and jazz-infused chords that gently sway back and forth (although they start out quite thin). He explores this for about 20 seconds and then returns to the opening material (00:22). This time he thickens up the chords before continuing with the counterpoint. This second mini-section is longer than the first, and explores a denser polyphonic texture. It all reduces to a single note by about 50 seconds in, and by 00:55, we’re back to the beginning.

This time, however, the counterpoint is introduced right away (I imagine that the composer, rightly, feels that another extended introduction to the main melody (not quite the right word) is unnecessary by this point in the piece). In this version, at 1:09, we hear a clear statement of what will become the glue for the B theme – a very simple but effective 3 eighth notes following the same pattern as in figure 1. Here it continues downwards, which will be another feature of the B section.

Finally, for A, we get a coda (ending section) where the first three notes of the main motive are repeated rising up to a new registral high-point, followed by a soft low note. This closes off the section and very quickly segues into B.

The first part of the B section is tied together by eighth notes rocking back and forth, but quickly expands into a middle line that has its own melody and character. The first thing I thought when I listened to it was that it reminded me of the Brahms Rhapsody in G-Minor (go to 00:50 for the specific moment, but listen to the whole piece!) – the constant eighth note motion ties things together there (and in the end of the development, where Brahms links it to the first theme). On top of this, Andriessen writes more big, rich chords (that still show a jazz influence). It’s a really nice section – especially when (at 1:53) the downwards scales (which I mentioned above) begin. At first, this descent is really brought out (in this recording, which features the composer), but becomes more subtly integrated as the section progresses.

We return to the start of the B section at about 2:13, with a return of the eighth notes, and again follow a different path in which the “glue” stays fairly static in terms of pitch (and rhythm). It finally transforms back into the A material (figure 1) at 2:44, and to a literal repeat of the beginning at 2:50(ish). This section is basically the same as the opening, so I won’t belabor the point.

I think the title fits the piece perfectly – it is totally reminiscent of a hot summer night in the city – a little lazy, a little jazzy…All in all, an attractive and tightly constructed piece that showed me a new side of a composer whose music I enjoy.

Did you enjoy it? Leave me a comment!

(biographical information from: http://www.boosey.com/pages/cr/composer/composer_main.asp?composerid=2690&ttype=BIOGRAPHY&ttitle=Biography)