This week we’re going to look at the last variation in the brass quintet. If we look back at what came before, we can see that I teased an ending that was a little like the beginning – solo trumpet juxtaposed with textural writing for the others (although this time it’s less textural and a little more contrapuntal). Instead of coming to an end (in a mysterious and ethereal way), which would be the logical course, it speeds up into this jazzy section that we’ll look at today.

If I had been writing this twenty (or more) years ago (or today in some institutions), the question of whether or not the “fun” nature of this last variation cheapened the whole and made it less than art-music probably would have been posed. Luckily we (mostly) live in a cultural period where there is much more cross-pollination from different genres of music. I’ll admit that there are going to be composers who would look down their noses at this section (actually, at the entire piece), but my mission for the variations was for a more light-hearted approach, and this ending is certainly light-hearted. I feel like if I’m addressing my musical goals in a way that’s true to myself and the music, then I’m not betraying some sort of “high-art” ideal. My philosophy will always be “use the techniques that benefit the end product,” not the other way around (the Machiavellian composer?).

So anyway, what we actually have here is a jazz rendition of the first strain of the Sousa. It begins with an introduction with some nice syncopation, and my favorite jazzy chord (seen in measure 247) which contains the root, seventh, and the major and minor thirds. For some reason, this says “jazz” to me more than any other chord. When the trumpet comes in with the melody (in jazzier rhythms), the other instruments support it with harmonies that are derived from the original Sousa.

To get those harmonies I used a couple of different techniques. The first of these is called Tritone Substitution. Let’s say you’re in C-Major. The dominant would be G-B-D-F. In jazz, it is pretty common practice to substitute a chord that’s exactly half an octave (or “tritone”) away. This works because it shares important common notes. In this example, the tritone substitution for G-B-D-F would be Db-F-Ab-Cb. Because the tendency tones (the B (or Cb) and the F) want to resolve to C and E, this makes the tritone substitution an effective substitute for a dominant chord – and much more colorful sounding. I didn’t restrict this substitution to dominants, but used it liberally throughout this section.

The other one, which is also well-represented in this variation, is the “what sounds good to me?” technique. I have the tune, and I’ve chosen where my tritone substitutions are going (mostly), and then I sit at the piano and play around with different chord choices until it seems to flow properly. I will admit to not being the most fluent person when it comes to jazz chords (it’s on my list of things-to-do!), so perhaps it could feel ‘jazzier’. At the moment, though, it feels fun and, well, a little groovy.

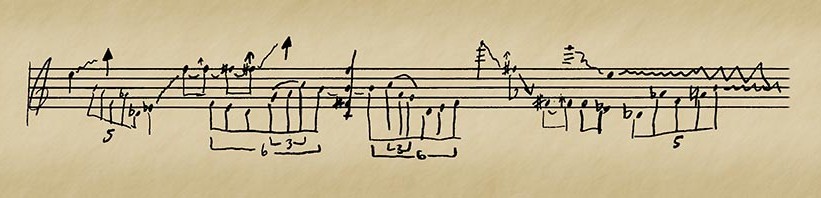

After we get through the Sousa, things really break out. In measure 267, I drop all pretense of whatever “high art” is these days and go into a sort of gospel chord progression (I-IV-I-IV). The individual lines are heavy on the chromatic movement that defined the Sousa (G-F#-G) in this case, and the second trumpet’s G-E-G clarifies the relation of the opening trumpet solo to the Sousa. The piece continues, becoming texturally denser while the first and second trumpets keep trading the focus between them. Slowly but surely, the harmonies become crunchier and more chromatic (with some more tritone substitution), until we reach a crisis point at 281, where the rhythmic density, the chromaticism, and textural density all combine to provoke a nice, big ending. The ending punches are spaced according to the number series in the “Aggressive” variation, and the sting on the end is entirely necessary!

I’m not sure that the transition from the crazy gospel rhythmic density section to this ending is right, but I haven’t worked out anything better yet. One thing I’m considering is having two free measures (or 4, perhaps) where I either give each part a chord (a different chord) and tell them to improvise based on the previous material around that chord, or to try to create some grand melange of all the previous variations. That latter choice would be very “me,” but I’m not sure how to execute it, or whether it would even work.

Here’s an extra problem, though – they’ve been playing for a long time. I fear that it’s going to be too much for even the most steely of brass players if I add a lot of stuff here. So I’m waffling. Do you have an opinion? Leave a comment!

Brass Quintet – Variation 5 – PDF

So that is the end of this series on the writing of the brass quintet. I had considered doing a post about revising, and I may still do that once I’ve had a little more time to sit and think about it, but as I did a lot of tweaking as I was writing these blog posts, you’ve seen most of the revisions in action. In any case – I hope you’ve enjoyed these forays into a fun and slightly mysterious set of variations based on the Washington Post march.

My next composition is going to be three short movements for piano solo. I haven’t really started writing them yet – perhaps we can take the journey together.