In the last post I discussed my thoughts and actions in setting the theme of my brass quintet (which still doesn’t have a name). As a theme, it serves as crucial generative material for the entire work–generative material that should be represented in the opening (at least, according to my writing preferences). That would be simple in a “normal” theme and variations, as the theme would be there as one of the first things the audience heard, proudly proclaiming the material that was to be iterated upon. This is more problematic in my “surprise!” theme and variations, since the theme is not heard until around the fifth minute of the piece.

The problem boils down to this: How do I provide the audience with something that gives them a clue about where we’re going without spoiling the destination? My answer was to take three elements from the Sousa, and combine them with techniques that I was planning to use in the variations…to give a sort of macrocosmic view of the piece in the first seventeen measures.

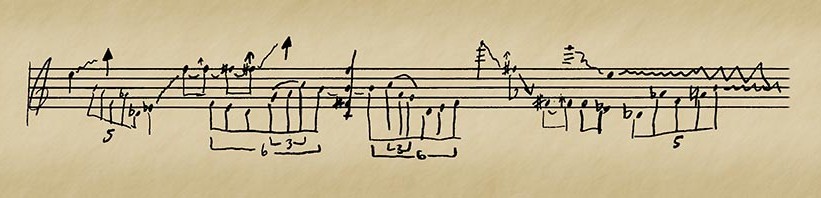

So let’s take a look at these things side by side:

Example 2 stands out, not because it is unintentionally larger than the others, but because it contains that chromatic motion that is so integral to the Sousa march. It plays a large part in my piece as well, and that is reflected in the beginning material, where the first and second trumpets have multiple chromatic inflections.

Example 1 is a little more obscure. It comes from the second strain of the march (you can find it in my rendering of the theme area in measures 160 and 162). Here, I have stretched the interval to a perfect fourth instead of a minor third. The second time the trumpet enters with this, in measure 3, it reverts to a minor third for a touch more veracity.

Finally, Example 3 is also from the second strain–the very end this time. Instead of putting this in the trumpets, I assigned it to the tuba as a bass line for the texture that follows the first trumpet’s opening notes. I think that this works nicely – if you look back after the piece is finished, you can see the connection, but it’s not giving anything away.

So what is happening in those textural sections? Well, the top and bottom voice are providing motivic material, and the middle voices are filling in the harmony. There’s basically a white-note cluster from G-F that sounds warm (to me, anyway). The conflation of the triple meter with the duplets foreshadows the dissolution of the theme that I discussed last time, while providing some rhythmic interest. So what we have to open the piece is:

Cold and slightly mysterious solo trumpet->warm polyrhythmic texture. I denote the trumpet as “cold” because I tend to think of the perfect fourth and minor second as “cold” intervals (I wrote an entire piece based on that notion, and it may appear here some day!)

We then have a similar section. You may remember that in my post on the first beginning I tried for the piece, I complained that I didn’t like having two sections that did “the same thing twice.” Here, I almost have that, but I avoid it by making some important changes. As I mentioned above, the perfect fourth of the first trumpet turns into a minor third and we get some F and C-sharps. This gives the texture a different feeling, even though it has basically the same rhythmic content.

From there, the piece starts to develop outwards (measure 6), with some interplay between the two trumpets, accompanied by a variation of the earlier texture. All of this is brought to a kind of stasis in measure 8 by the introduction of the beginning of the theme in the second trumpet (F-F-E-F-G)(see example 2). There is a pause for consideration, and the piece seems to restart (a little lower). This time, however, the texture is missing, and we hear an almost chorale-like idea that is developed in measure 14, where I make an effort to keep instruments from changing pitch on the same beat. This is important to keep the rhythmic flow moving, and also to set up a technique that I will use much later in the piece.

The beginning ends with an agreement on a G-Minor chord (that will lead to a C – shocking!). The first variation is very different and will use the horn line that I developed for my failed beginning.

Why does this work for me where the other beginning didn’t? I’m not sure that it’s “fun” per se, but I think it is mysterious without being ominous. It has a few hints about the theme, and combines them with other hints about the techniques I’ll be utilizing in the variations themselves. There’s nothing too “crunchy” in the harmonic language, and we approach some sort of triadic moment at the end. I’m okay with that – there are plenty of nicely dissonant moments throughout the piece – I’ve always felt that implications of tonality or triadic writing shouldn’t be avoided if they feel right for the piece, and that they can live together with more atonal (or non-tonal) sections if prepared properly. That’s the trick, though.

Thoughts? Comments? I’d love to hear from you! I graduate soon, and will be away for a little while, but next time we’ll look at the first variation, which, to whet your appetites, is entitled “Quirky.”